|

With no written language, Aboriginal cultures have

maintained their customs, myths, and legends through ceremony and a

deeply seated verbal tradition. Tribal lore is passed on by

storytelling, and important stories are memorized and handed down to new

generations by clan elders. As young men mature and gain prestige within

their clan, they are entrusted with specific tales known as “dreamings”,

and are considered to be the guardian of these stories until they pass

them on to the next generation. This holds true for artwork as well.

Artists “inherit” stories, themes, and characters from their tribal

group, which can be illustrated by no-one else. These inherited

characters and stories strongly influence an artist’s work, and are

repeated and embellished throughout the artist’s life. With no written language, Aboriginal cultures have

maintained their customs, myths, and legends through ceremony and a

deeply seated verbal tradition. Tribal lore is passed on by

storytelling, and important stories are memorized and handed down to new

generations by clan elders. As young men mature and gain prestige within

their clan, they are entrusted with specific tales known as “dreamings”,

and are considered to be the guardian of these stories until they pass

them on to the next generation. This holds true for artwork as well.

Artists “inherit” stories, themes, and characters from their tribal

group, which can be illustrated by no-one else. These inherited

characters and stories strongly influence an artist’s work, and are

repeated and embellished throughout the artist’s life.

|

|

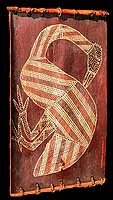

As

well as painting on stone, Aboriginal artists also painted on Eucalyptus

bark, dried and flattened over an open fire. This tradition began before

the European settlement of Australia in the 1700s. Due to their

temporary nature, most early works have been destroyed by age and

weather, and the date the style began is unknown. Painting on bark may

have begun with Aboriginal artists painting the interiors of their bark

shelters in a manner similar to painting in caves, or with the painting

of shields, weapons, and other personal objects. The use of flattened

bark increased in the 1920s with requests from outsiders for work that

could be easily transported. This technique worked, but the bark

paintings often warp or crack from drying and stress. As

well as painting on stone, Aboriginal artists also painted on Eucalyptus

bark, dried and flattened over an open fire. This tradition began before

the European settlement of Australia in the 1700s. Due to their

temporary nature, most early works have been destroyed by age and

weather, and the date the style began is unknown. Painting on bark may

have begun with Aboriginal artists painting the interiors of their bark

shelters in a manner similar to painting in caves, or with the painting

of shields, weapons, and other personal objects. The use of flattened

bark increased in the 1920s with requests from outsiders for work that

could be easily transported. This technique worked, but the bark

paintings often warp or crack from drying and stress.

|

|

Since the 1960s the introduction of oil and acrylic

paints, canvas, printmaking techniques, and high quality papers has

caused a revolution in Aboriginal art, providing Aboriginal artists with

powerful tools to visualize their rich culture and tradition. In 1990

high quality rag paper and archival watercolors were introduced to

artists working at Injalak. The paper was quickly accepted as an

alternative to painting on bark, and a technique was developed using

watercolors to create rich, layered backgrounds. Despite the

availability of modern materials, artists chose to continue to use

traditional ochre pigments to create the detailed drawings that are the

focal point of each piece.

|

|

The

new materials introduced at Injalak were part of an attempt to create a

visual record of rapidly disappearing Aboriginal traditions. The

European colonization of Australia that began with the exile of English

prisoners in the 1700s, decimated the indigenous population through

warfare, forced enculturation, and disease, and reduced the population

from an estimated 3 million in 1700 to a quarter of a million today.

Modern Australian culture continues to change Aboriginal life, with many

young people leaving their clans and traditional lands to find work in

the cities. As a result many “dreamings” are in danger of being lost

forever. Organizations like the Injalak Art Center are working hard to

enable Aboriginal artists to take pride in their heritage, to recognize

the value of their culture, and to preserve one of the world’s oldest

and most unique artistic traditions. The

new materials introduced at Injalak were part of an attempt to create a

visual record of rapidly disappearing Aboriginal traditions. The

European colonization of Australia that began with the exile of English

prisoners in the 1700s, decimated the indigenous population through

warfare, forced enculturation, and disease, and reduced the population

from an estimated 3 million in 1700 to a quarter of a million today.

Modern Australian culture continues to change Aboriginal life, with many

young people leaving their clans and traditional lands to find work in

the cities. As a result many “dreamings” are in danger of being lost

forever. Organizations like the Injalak Art Center are working hard to

enable Aboriginal artists to take pride in their heritage, to recognize

the value of their culture, and to preserve one of the world’s oldest

and most unique artistic traditions.

While in Oenpelli, Bock and Garland acquired a

select grouping of original works from the artists working at Injalak.

These works, along with original photography documenting their journey

and the ancient rock art of the region, are available for viewing at the

Williams Gallery West in Oakhurst. |

|

CLICK

HERE To

return to page 1 |

CLICK

HERE To

view our catalog of Aboriginal Art |

![]()